Hello, everyone! Standing at the end of 2023, I would like to update and summarise the most recent research with you.

In this update, you will read the major topics as follows:

- Circular matchmaking model is submitted for publication review;

- Link the model outcomes with practical insights;

- Preliminary model evaluation for educational purposes;

- Final phase of PhD: One more year to go.

1.Circular Matchmaking Model

The model is developed and submitted for publication. We are now waiting for the reviewer’s comments. The research article contains key points as follows:

- Agent architecture based on Shearing Layers;

- Matchmaking logic based on dynamic matching;

- Potential urban development scenarios in Enschede.

A summary of each point is given one by one in this update. We will share a final version of the article with you after it goes through the reviewing process. Now you can find more technical details about the developed model in the ODD Report.

1.1. Agent architecture

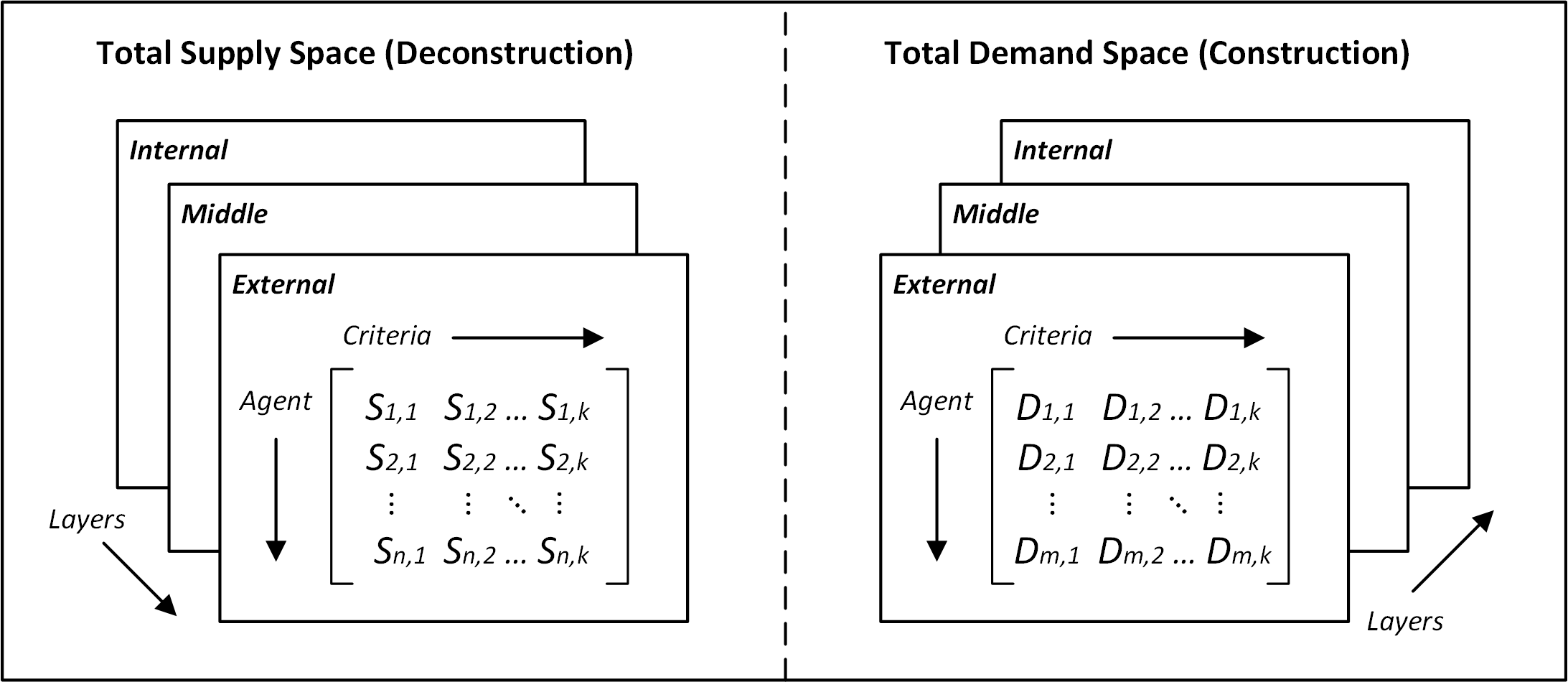

To capture the internal complexity of building projects, we draw on the seminal work of Brand (1994) that depicted buildings as a collection of shearing layers each with its life cycle. Adapted from the original setup of shearing layers, we propose three overarching layers to design agent architecture as follows (Fig. 2):

Fig.2. Agent architecture based on shearing layers: S and D stand for Supply and Demand agents, respectively. The total numbers of supply and demand agents are n and m, respectively. Suppose there are k types of matchmaking criteria, the matrix entails the total matchmaking space. For example, S1,1 means the first criteria of the first supply agent.

Fig.2. Agent architecture based on shearing layers: S and D stand for Supply and Demand agents, respectively. The total numbers of supply and demand agents are n and m, respectively. Suppose there are k types of matchmaking criteria, the matrix entails the total matchmaking space. For example, S1,1 means the first criteria of the first supply agent.

- Internal Layer (I): Stuff (e.g., furniture);

- Middle Layer (II): Services and Space plan (e.g., floors and doors);

- External Layer (III): Site, Structure, and Skin (e.g., external walls and load-bearing elements).

This is a simplified version of Shearing Layers that captures the workflow complexity of a building project. The key reason for constructing building layers in such a way is that the main contractors of deconstruction and construction projects shall plan their workflows in the opposite order (i.e., deconstruction: I, II, III, and construction: III, II, I). Accordingly, what is available first from a deconstruction site could be the last item that is required by another construction firm. For example, deconstruction contractors first remove furniture out of old buildings while construction contractors need to first build foundations for new buildings.

“This setup makes temporal supply-demand mismatch among different projects explicit in the model.”

1.2. Matchmaking Logic

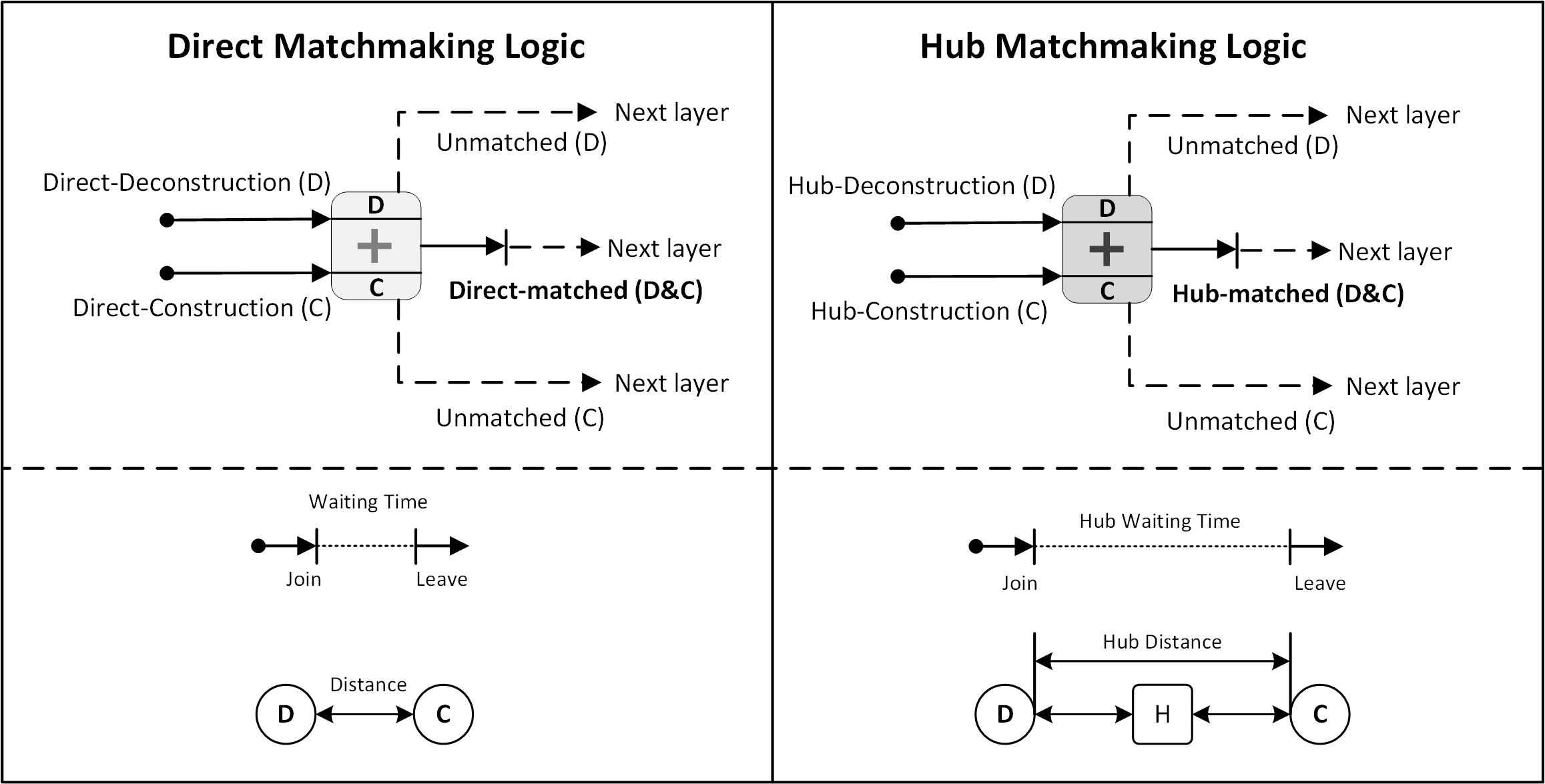

The matchmaking logic is adapted from the prior work of dynamic matching with stochastic arrivals under limited sojourn/waiting time (Fig. 3). We consider not only (1) when a building is ready to be deconstructed after reaching the End-of-Life phase, but also (2) how long this offer of reusable/recyclable waste stays available (waiting time) on the market. This is a classical operation research concept applied to practical marching problems like carpooling and medical operations (e.g., organ matching priority) (Akbarpour et al. 2019; Aouad & Saritac 2022). This timing setup helps to capture more realistic matchmaking dynamics through different levels of detail.

Fig.3. Matchmaking logic: (A) -- Matchmaking logic comparison where hubs provide extra waiting time and allow larger transportation distances; (B) -- Opposite matchmaking order at three shearing layers; (C) -- Visualisation of project agents at GIS points in the modelling context

Fig.3. Matchmaking logic: (A) -- Matchmaking logic comparison where hubs provide extra waiting time and allow larger transportation distances; (B) -- Opposite matchmaking order at three shearing layers; (C) -- Visualisation of project agents at GIS points in the modelling context

Once the simulation runs, project agents continuously update their ages. When the age exceeds the predefined age threshold (75 years in this case), agents make stochastic decisions and participate in the matchmaking program. The matchmaking programme matches a pair of agents whose supply-demand requirements are similar regarding the supply-demand costs, the supply-demand quantities, and the transportation distance between the two projects. Notably, these supply-demand offers would only be available for a limited time (sojourn time). If there is no suitable match within the sojourn time, agents must leave the programme and continue to seek partners at the next layer.

Project agents receive results from the matchmaking programme and update their visual characteristics (i.e., colour and transparency) accordingly. The final ending colours are green and grey indicating successful and failed matchmaking, respectively. Project agents continue to matchmake at the next layer until (1) all shearing layers are successfully matched or (2) a maximum rejoining frequency is reached. The variables of project agents, matchmaking status plots, and the model interface are updated simultaneously.

1.3. Urban Development Case

The construction demand baseline consists of five major real-estate projects above adding up to 1914 residential units. These projects are: (1) De Kop, (2) Janninkkwartier, (3) Cromhoff, (4) Eschmarkerveld, and (5) Het Leuriks. Meanwhile, 2000 existing residential buildings in Enschede are randomly selected based on the BAG database serving as a deconstruction supply baseline. Unlike deconstruction projects scattered in the city, construction projects are planned within specific locations. Adding to the opposite internal workflows defined at an individual agent level, this spatial setup creates special supply-demand flows at an urban level.

“Deconstruction projects tend to spread reusable components in a divergent manner while construction projects would receive different components in a convergent manner.”

Adding to the urban development case, we introduce Circularity Hubs as a matchmaking moderator. These hubs are potential warehouses that could offer temporary storage, repair, cleaning, and sorting services. Stakeholders can also use them as buffering stations to collect materials until a sufficient quantity is available for economical deals. Please refer to the previous blog for a hub conceptual diagram. In this research, we created five potential hubs around the ring road of Enschede and tested their effects on matchmaking status. This setup helps to compare hub effects on diverse urban areas in different directions. They provide (1) longer sojourn/waiting time and (2) larger transportation ranges for matchmaking.

The simulation shows how supply-demand (mis)matches evolves over space and time. To access and interact with the model by yourself, you can use this Link. You can also directly play and observe it here as follows (click "full-screen" button to have better viewing experience):

2. Practical Insights

According to the case, construction agents need to accomplish their projects within the next 5 years approximately. There is a great construction demand in a relatively short time. However, the supply provided by deconstruction agents emerges stochastically at a slower pace. Since the supply is not temporally dependent on the demand, the supply from existing buildings can hardly meet the demand of construction projects based on the current scenario setup. Therefore, most project agents remain unmatched or matched incompletely at the end of the simulation.

The dynamics of IS matchmaking can be observed by comparing the changes of the agent's colour in snapshots. Existing buildings are scattered around the city while new buildings await to be built at limited target sites. This shows an operational conflict that deconstruction supply could originate from all over the place but construction demand usually occurs within a narrow spatial range. Moreover, the quantity mismatch complicates this situation. The supply from an individual building can hardly be comparable, in the sense of quantity, with the demand of an integrated project including clusters of buildings.

The simulation results conceptually proved that circularity hubs contribute to successful matchmaking. Larger transportation ranges link projects that cannot interact with each other without hubs. Longer sojourn time creates more opportunities to wait for a suitable partner. Meanwhile, a competitive hub market appears when multiple hubs operate simultaneously. Hubs compete with each other and the most advantageous hub would dominate the market.

Therefore, under this simulation scenario, results quantitatively suggest that:

"A higher number of hubs does not necessarily contribute to a higher successful matchmaking rate. Instead, strategic hub allocation considering the spatial distribution of heterogeneous project agents is the key to effective matchmaking."

However, these are conceptual results only considering limited aspects of matchmaking. In practice, longer waiting time also indicates higher transaction investments, which would interrupt a matchmaking event. The practical hub operation remains a future research topic.

3. Preliminary Model Evaluation With Students

Our model is NOT designed to accurately support practical decisions based on robust real-time data. Instead, we develop this model to create a new perspective to study a possible phenomenon that can hardly be observed in reality. Therefore, we evaluate the model and aim to understand how it could help circular economy learning. The evaluation is carried out in the form of a workshop with a group of Master students on campus:

- Design background introduction and explanation;

- Students-model interaction and observation;

- Discussion and fill in the evaluation form.

You can check the evaluation form via this Link.

Generally, students agree that this is an interesting model that helps to understand the complexity of the circular built environment. The model links the internal complex workflows of each project with external material-exchange flows through different levels of detail. It provides a bird's view of circular matchmaking dynamics over vast space and time dimensions.

However, students also observed that there is a certain distance between the model and the reality. For example, agent behaviours are linear and simple in the model whereas the motivations for demolition and circular collaborations can be complex in reality. Quality is simplified as a numerical factor in the model, however, it could be a focal factor for successful matchmaking. Despite the model's limitations, we concluded that it can serve as an educational tool for students to study broad circular economy landscapes in the built environment beyond the boundary of an individual building project.

4. Final Phase of PhD

More than the PhD work, we are also actively involved in (click them for more details):

- Educational innovation: Circular Economy Transition Minor;

- Grant acquisition: Industrial Symbiosis To Hubs For Circularity;

- Community development: Circular Economy Platform Twente;

- Future research: Circular Twente Campus.

Starting in January 2024, I will wrap up all the research components and focus on the final thesis book. Rooted in the circular built environment, this book:

- Discovers new relationships between digital technology, policy-making cycle, and circular built environment;

- Showcases new design evidence of a Circularity Information Platform at strategic and operational levels;

- Advances a new paradigm of smart circular construction ecosystems for scientific research.

Overall, this research motivates, designs, demonstrates, and evaluates the Circularity Information Platform towards a circular built environment. It provides theoretical and practical guidance to manage multiple construction projects as circular material ecosystems in a broader spatial-temporal scope beyond the boundary of an individual project.

We propose a new theory to manage circular building projects at scale.

After my graduation, I aim for a researcher position at the UTwente. We will be sure to keep in touch with you for potential evaluation and expert opinions in the upcoming year. Meanwhile, please do not hesitate to contact us if you have any questions or want to talk about future research opportunities!

Thank you, everyone! I wish you all a great happy new year 2024! Success!